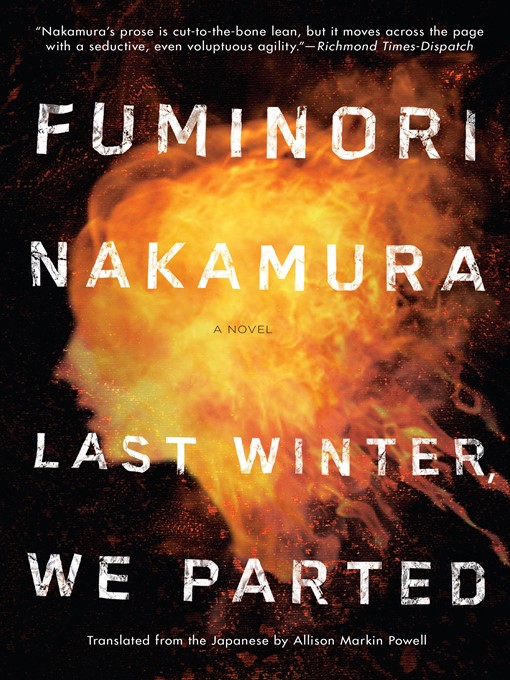

Instantly reminiscent of the work of Osamu Dazai and Patricia Highsmith, Fuminori Nakamura’s latest novel is a dark and twisting house of mirrors that philosophically explores the violence of aesthetics and the horrors of identity.

A young writer arrives at a prison to interview a convict. The writer has been commissioned to write a full account of the case, from the bizarre and grisly details of the crime to the nature of the man behind it. The suspect, a world-renowned photographer named Kiharazaka, has a deeply unsettling portfolio—lurking beneath the surface of each photograph is an acutely obsessive fascination with his subject.He stands accused of murdering two women—both burned alive—and will likely face the death penalty. But something isn’t quite right. As the young writer probes further, his doubts about this man as a killer intensify, and he struggles to maintain his sense of reason and justice. Is Kiharazaka truly guilty, or will he die to protect someone else?

Evoking Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and Ryūnosuke Akutagawa’s “Hell Screen,” Last Winter, We Parted is a twisted tale that asks a deceptively sinister question: Is it possible to truly capture the essence of another human being?