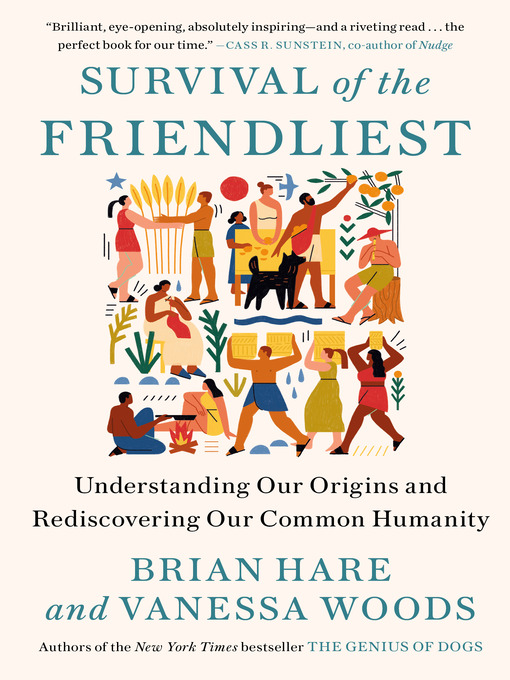

“Brilliant, eye-opening, and absolutely inspiring—and a riveting read. Hare and Woods have written the perfect book for our time.”—Cass R. Sunstein, author of How Change Happens and co-author of Nudge

For most of the approximately 300,000 years that Homo sapiens have existed, we have shared the planet with at least four other types of humans. All of these were smart, strong, and inventive. But around 50,000 years ago, Homo sapiens made a cognitive leap that gave us an edge over other species. What happened?

Since Charles Darwin wrote about “evolutionary fitness,” the idea of fitness has been confused with physical strength, tactical brilliance, and aggression. In fact, what made us evolutionarily fit was a remarkable kind of friendliness, a virtuosic ability to coordinate and communicate with others that allowed us to achieve all the cultural and technical marvels in human history. Advancing what they call the “self-domestication theory,” Brian Hare, professor in the department of evolutionary anthropology and the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience at Duke University and his wife, Vanessa Woods, a research scientist and award-winning journalist, shed light on the mysterious leap in human cognition that allowed Homo sapiens to thrive.

But this gift for friendliness came at a cost. Just as a mother bear is most dangerous around her cubs, we are at our most dangerous when someone we love is threatened by an “outsider.” The threatening outsider is demoted to sub-human, fair game for our worst instincts. Hare’s groundbreaking research, developed in close coordination with Richard Wrangham and Michael Tomasello, giants in the field of cognitive evolution, reveals that the same traits that make us the most tolerant species on the planet also make us the cruelest.

Survival of the Friendliest offers us a new way to look at our cultural as well as cognitive evolution and sends a clear message: In order to survive and even to flourish, we need to expand our definition of who belongs.

-

Creators

-

Publisher

-

Release date

July 14, 2020 -

Formats

-

Kindle Book

-

OverDrive Read

- ISBN: 9780399590672

-

EPUB ebook

- ISBN: 9780399590672

- File size: 14505 KB

-

-

Accessibility

-

Languages

- English

-

Reviews

Loading

Formats

- Kindle Book

- OverDrive Read

- EPUB ebook

subjects

Languages

- English

Why is availability limited?

×Availability can change throughout the month based on the library's budget. You can still place a hold on the title, and your hold will be automatically filled as soon as the title is available again.

The Kindle Book format for this title is not supported on:

×Read-along ebook

×The OverDrive Read format of this ebook has professional narration that plays while you read in your browser. Learn more here.