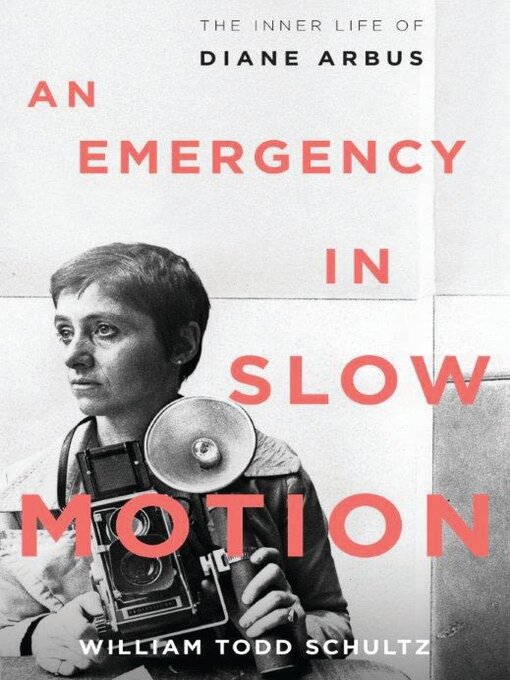

In the spirit of Janet Malcolm's classic examination of Sylvia Plath, The Silent Woman, William Todd Schultz's An Emergency in Slow Motion reveals the creative and personal struggles of Diane Arbus. Schultz, an expert in personality psychology, veers from traditional biography to look at Arbus's life through the prism of five central mysteries: her childhood, her outcast affinity, her sexuality, her time in therapy, and her suicide. He seeks not to give Arbus some definitive diagnosis, but to ponder some of the private motives behind her public works and acts. In this approach, Schultz not only goes deeper into her life than any previous writing, but provides a template to think about the creative life in general.

Schultz's careful analysis is informed, in part, by the recent release of Arbus's writing by her estate, as well as interviews with Arbus's last therapist. An Emergency in Slow Motion combines new revelations and breathtaking insights into a must-read psychobiography about a monumental artist — the first new look at Arbus in 25 years.

-

Creators

-

Publisher

-

Release date

September 6, 2011 -

Formats

-

Kindle Book

-

OverDrive Read

- ISBN: 9781608196814

-

EPUB ebook

- ISBN: 9781608196814

- File size: 753 KB

-

-

Languages

- English

-

Reviews

-

Publisher's Weekly

May 16, 2011

Schultz's biography of the talented, deeply troubled photographer Diane Arbus, who committed suicide in 1971, takes the form of an ambitious "psychobiography"âan account of Arbus's inner life in which he regards her photographs through the lens of psychological theory to speculate on her motivations and obsessions. It is the first account of Arbus's life since Patricia Bosworth's acclaimed Diane Arbus in 1989, and Schultz (editor of the Handbook of Psychobiography) makes good use of biographical material released by the Arbus estate since Bosworth's bookâas well as interviews with Arbus's psychotherapistâto shed new light on the photographer's artistic aims, particularly her choice of subject matter: transvestites, circus performers, "freaks." He argues, for example, that Arbus's obsession with twins, whether literal twins or mirror images and doppelgängers, was an expression of her own psychological defense mechanisms. "The bad and the good," he writes, "are kept far apart to protect the good from infiltration." Ideally, this approach of using the work to speculate on the artist's psyche would yield some fresh insight into the work itself. Instead, Schultz's interpretations of Arbus's photographs can be repetitive and shallow. Nonetheless, his sensitivity to Arbus's inner life and the links between mental illness and creativity make this a provocative, if not always persuasive, addition to the literature on Arbus. -

Kirkus

June 15, 2011

A theorist of psychobiography offers an example of his favored approach in an exploration of a most perplexing figure, the edgy and controversial photographer Diane Arbus (1923–1971).

Arbus provides a promising canvas for Schultz, who's also written about Truman Capote (Tiny Terror, 2011). He sketches the privileged childhood of Arbus, whose brother was poet Howard Nemerov (the talented siblings engaged in a little youthful sex play, says Schultz), and highlights the significance of an early memory of seeing a shantytown. The author moves briskly through her career, returning continually to the notion that as Arbus' subject were often freaks, so she, too, was one. He dusts off the familiar notion that her photographs are generally about herself—she sought herself, reflected herself, found herself in others. Her final group of subjects—the mentally retarded—she found frustrating to work with, writes Schultz, because she could not elicit from them the interactions she found so essential. The author also focuses on Arbus' sex life, noting how frequently she posed her subjects in their beds (including TV icons Ozzie and Harriet in 1971) and how she sometimes engaged in sex acts with the people she was photographing. She seduced her subjects, writes Schultz, sometimes in multiple ways. An exception was Germaine Greer; their session was a remarkable struggle of wills, which Greer won. Arbus had one failed marriage, a late-life affair that didn't work out, countless sex partners, a battle with hepatitis, an odd course of psychotherapy and issues with cash flow—all culminating in the stress and depression that led to her suicide. Schultz writes in detail about her death and remains uncertain if she fully intended to kill herself.

Though sometimes clanging with psychological jargon, a biography that wisely recognizes the ultimate mystery of every life.(COPYRIGHT (2011) KIRKUS REVIEWS/NIELSEN BUSINESS MEDIA, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.)

-

Formats

- Kindle Book

- OverDrive Read

- EPUB ebook

Languages

- English

Loading

Why is availability limited?

×Availability can change throughout the month based on the library's budget. You can still place a hold on the title, and your hold will be automatically filled as soon as the title is available again.

The Kindle Book format for this title is not supported on:

×Read-along ebook

×The OverDrive Read format of this ebook has professional narration that plays while you read in your browser. Learn more here.